9

On January 1st, 1992, I watch the Miami Hurricanes defeat the Nebraska Cornhuskers 22-0 in the Orange Bowl and win the National Championship. The game is marred by a severe thunderstorm and only one camera filming the game works. Four days later my father and I load up the 4Runner and drive to West Palm Beach from NY.

UM Campus

Before going down, I call the Athletic Department, asking them to house me in the athletic dorms. Since I’m not a scholarship player, it isn't possible. Instead, I’ll be housed in a dorm reserved for juniors and seniors, meaning the dorm is all about being chill and quiet.

I was the only kid I knew who was going to a college they had never visited. While my father and I drove by the University of Miami a year earlier, we never actually entered the campus. Some might say going to a college you’d yet to visit, especially one 1200 miles from home, might not be a good idea. Kids from my town toured five or six colleges before deciding. For some of them, choosing was a process which consumed them since middle school.

Not me.

Even when it came to football, I didn’t have a favorite college team (though of course I did really like Miami, but remember we played football Saturday afternoons. The only collge football I got to watch were Saturday night games and the bowl games on Jan 1st). I didn’t have alumni parents pushing me in a predetermined direction. My sister went to college in Switzerland. When I was a freshman, I went to a Penn State football game because a friend’s father was a dedicated alumnus (PSU was one of the schools my mother secretly applied to. After my junior year, many people thought PSU, Pitt, or Syracuse was where I would end up playing football). Other than The Naval Academy and West Point, That trip to Happy Valley was the only time I had visited a major university campus.

With Miami, you didn’t just get a campus, you got a city. A great city. I was about to be exposed to a new reality. Rather than cloistering myself away at some small North Eastern college tucked away in some little college town where everything centered around the school and its prevailing white culture, I was going to be immersed in a multicultural, international city full of palm trees, danger, weirdness, and warmth.

Warmth.

As we drove south on I-95 it was amazing to see the weather change and get warmer and warmer. When we saw the first palm tree somewhere in South Carolina, a huge smile spread across my face. When we hit Jacksonville and entered the Sunshine State, I knew without a doubt that a place where winter never touched was the place for me.

I had been to the city of Miami a few times but never more than a few hours. I’d been to Miami Beach and Joe’s Stonecrabs once. The first time I saw the city at night that January, glistening under a full moon, warm breezes rustling the palms, the smell of the ocean in the air, AND NOT HAVING TO BE BUNDLED UP, I didn’t think I was in heaven, I KNEW I was in heaven.

Miami was the right place for me. The city pulse—you could feel. How could I ever have even thought about going anywhere else? It had been a strange path, but it ended up in the perfect place.

The UM campus is one of the nicest campuses you’ll ever see, and it’s small (UM when I attended had around 12,000 undergrads and another 3,000 grad). Called the ‘University of Miami’, but technically in Coral Gables, the campus is self-contained, only sprawling a little bit beyond it’s boundaries. As for Coral Gables, it’s a beautiful town with multitude of homes designed by Mizner, the legendary architect who blended Spanish Moorish, New Americana and Latin flare. Coral Gables’ claim to fame is that it’s the first planned residential community in America. Essentially, it was America’s first gated community, a giant town created where there was nothing before.

To add to the greatness of the whole situation, Coconut Grove abutted The Gables. An artists colony and the highest point in Miami where pirates once lived, ‘The Grove’ was where you mostly hung out if attending UM. South Beach was far and just starting to get going again after being dormant for many years. There was really only one bar on Ocean Drive Whiskey Tango. It was rundown and had a pool table. They didn’t card anyone. I loved that place. Next door, elderly people sat in wheelchairs on the porch of their retirement home dressed in bed clothes.

So my father sets me up pretty good, we even buy a bike (which is stolen in one day). My dorm is right on Lake Osceola; a little body of water right in the middle of campus. My room is on the 4th floor, lake view. My roommate-to-be wasn’t back yet from winter break, but by seeing his stuff, he seemed like he could be cool enough. And when I say his ‘stuff’, I mean to say he had practically nothing in the room. Not even a TV, which thankfully I had brought with a SEGA Genesis. He didn’t even have a CD player, which again, I had. The room was stark and cold with two powerful air conditioners. A bathroom connected to another dorm room. In the other room was a strange senior I hardly talked to and Australian student studying Marine Bio. Neither had gone home for Winter break (unlike other dorms, this ‘residential hall’ as it was called stayed open over break). The Aussi and his two Aussi buddies became good friends of mine within a few days. Their love of beer and hard drinking fit right in with my life philosophy of fun first, school second, or third, maybe even fourth if at all. Plus I had a car. They were now mobile.

Orientation was boring, but I was just happy to be at college, though, once again, I was out of phase with the typical experience by coming in a semester late. One day I changed outfits three times for three orientations, finally settling on a pair of lizard skin cowboy boots, ripped light blue jeans, and a green paisley shirt with Indian Motorcycle baseball hat. I had zero Miami vibe going on with my wardrobe, though I did bounce my beloved Timberlands. At night I wore jeans, sneakers, and a patterned button-down shirt with a t-shirt underneath. For shorts I had to take scissors to a pair of jeans and cargo pants. One of the seniors working orientation lived on my floor. She was a UM cheerleader. A very pretty blond girl from northern FL who chatted me up nonstop and was more bubbly than a magnum of Champagne. She invited me over to her room. There I was, just about to turn 19, first few days at college, laying on a 22-year-olds bed who happened to be a hot little cheerleader for the football team.

Great set up for something exciting to happen, right?

Wrong.

I had no game. I mean none. A girl had to practically throw herself at me if anything was going to happen because lords know I wasn’t going to be making any first moves. Or, I had to know without doubt to the square-root of 100% positive that she liked me and wanted me to make a move. It wasn’t really about fear of rejection, it was about the fact that I was very conscious of not wanting to make girls uncomfortable when in my presence. Girls always said things like: I feel so safe around you, I feel so comfortable with you. How could I break that trust by making a move? Sometimes that ‘feeling safe and comfortable’ can turn into something more, but for me it was about not being an aggressive asshole. That aggressive asshole also tends to get a lot of action. I wasn’t a player. If I liked a girl, I wanted to take her out for dinner. Get to know her. Also, I’m a bit lacking when it comes to recognizing certain social cues. Those subtle cues we humans give each other to convey feelings are sometimes lost on me. On top of this, she lived on the same floor around the corner. One false move could be bad for my reputation.

So there I was laying on a bed with a very cute blonde cheerleader wearing midriff pajamas making light sexual references and waiting for me to make a move. But instead of doing anything, I wondered why such a hot girl would want me. I went through a checklist: I can be entertaining and funny, girls like that. I’m a good enough looking guy. Courteous. Nice but also with an outlaw streak. Instead of something exciting happening, we sat there awkwardly as I convinced myself there was no way she liked me and that to make a move would be a big mistake. (This wouldn’t be the last time I missed out on hot cheerleader action as you will find out later.)

The next night I gathered the courage, rented a movie, get a box of Rasinets and two bottles of 7UP, thought we could snuggle and then I would make a move. When I knocked on her door, a guy answered. I did an about face. I hardly saw her again.

One of the first things I did when I got on campus was to go over to the Hecht Athletic Center—the home of the Miami Hurricanes football team and the seat of sports power at the ‘U’ (for the record, the ‘U’ wasn’t a term used in the early ‘90s at all as I remember it).

Back then the complex was underwhelming and in need of some serious upgrades, but it was this very same lack of flair that gave it character. Also, the whole complex was pretty much wide open to the public with the exception being the locker-room and weight room. There was only one unlocked door on the second floor separating day-to-day Athletic Department office space from the coaches offices, meeting rooms, and football administration. I told reception I was a recruited walk-on, was here to meet a coach and start my compliance paperwork. Before trying out, they had to make sure I was eligible, which of course I was. Then I met the graduate assistant who would be handling walk-ons. His name was Greg Mark, a great defensive end who played for Miami in the late ‘80s. Getting hold of him was not easy, but finally I caught him sitting in his little windowless office.

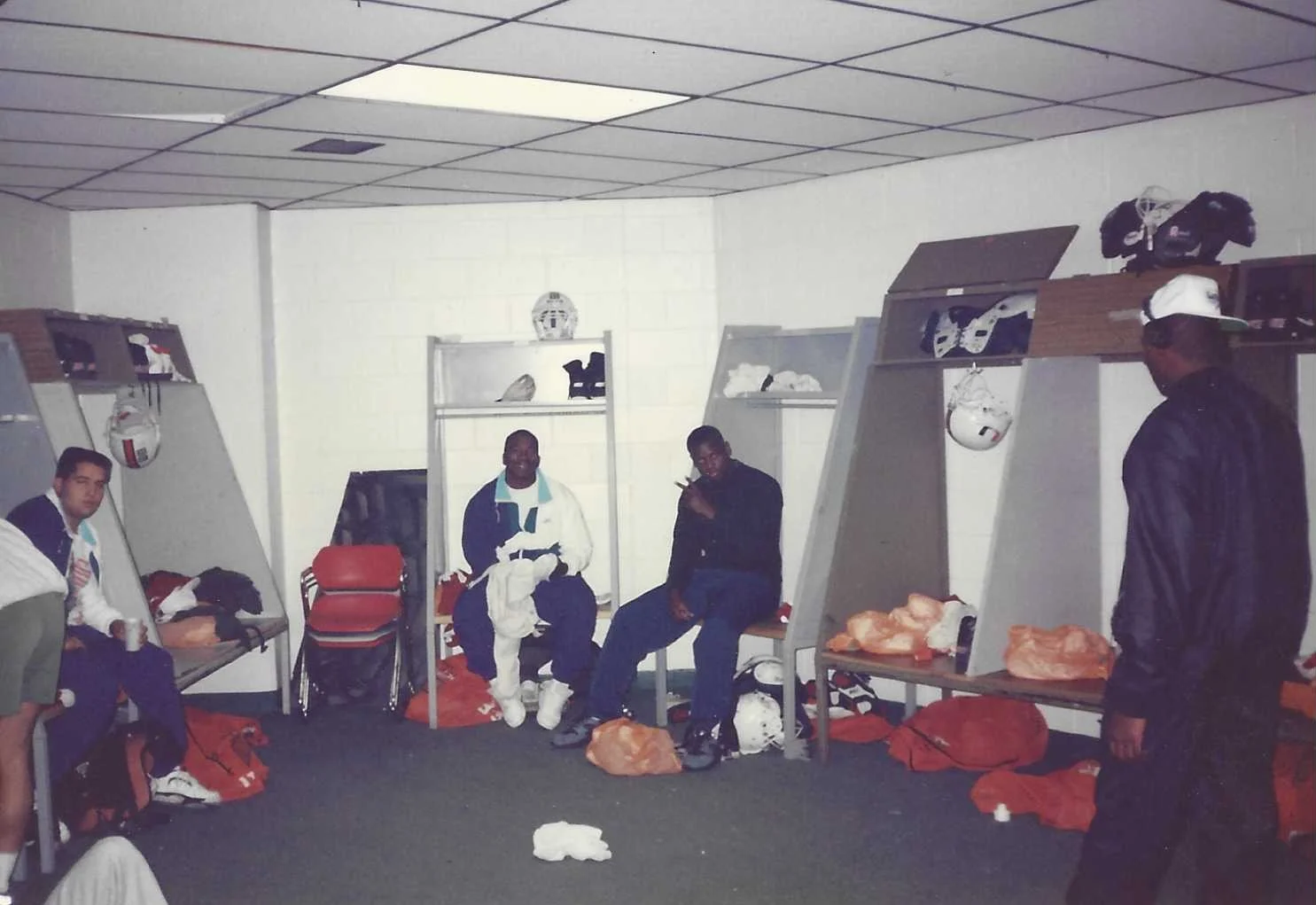

Coach Mark and future 1st pick by the Dallas Cowboys Russel Marryland who won 3 superbowls

For me, the prospect of being on the Hurricanes was the biggest deal in the world. To everyone else at Miami, including Coach Mark, it meant nothing. I wasn’t some big time recruit who would be welcomed with open arms. Nobody but me cared if I was on the team or not. I was excited. I couldn’t contain it. But Coach Mark, sitting there, spitting dip juice into a cup, while not blowing me off, simply told me to show up on February 25th for walk-on tryouts. Spring football would be starting right after spring break in mid March. I had a hundred questions, but focused on what that tryout entailed.

Just a weigh-in and running test, he said.

What is the test like? (I had been practicing 100-yard sprints all Fall on a local field. I hated every second of it, but at least I wouldn’t be going in cold.)

100-yard sprints. 16 of them. Timed.

Oh…shit.

After the running test, Coach Erickson will review the list and decide who to take…if anyone.

If anyone.

Those two words ricocheted around my mind.

There was a chance I would not make the team. I had never even once considered such a possibility. And the fact that the tryout was only a running test? I thought we’d be having some kind of two or three day tryout where we’d get to show our football abilities. If my running skills and endurance were the only things that would get me on the team, I was in trouble. Big trouble.

Next I went to the weight room. I was nervous as all hell. The strength coach’s name was Coach Role. A short, stocky man who was a funny hardass more than a few cards short of a full deck.

You’re a what? He said to me when I told him I was a new invited walk-on. You ain’t done nothin’ yet. You can’t work out here until you are on the team. The best he would do, after some pleading on my part, was to give me the orange UM Football workout binder. Sitting in the corner of his office were boxes of Hot Stuff. It had been taken off the market and Role stocked up on all he could find.

Next order of business was school and my major. Some kids think about their major day and night for years before attending college. I thought about mine for two minutes. Sitting there with the academic advisor, going over a list of possible majors, I stopped him on Architectural Engineering (AE). A five-year program giving a student a Bachelor of Science; AE was a difficult program to get into. They only took 60 new students every year out of hundreds who apply. To this day I wonder how I got into that program. The only thing I come up with is that since even though I wasn’t yet on the football team, academically I was a football player because all my information came through the athletic department. And I also made sure to mention to every administrator I came across that I was a football player. Maybe football players got some kind of preference? Ya think?

The drawback of getting into a very difficult major that I pointed to in the catalog because it sounded cool, was that I had absolutely NO BUSINESS BEING IN AE. None. I was stuck in Geometry 2 in high school. Now I would be taking trigonometry, physics, calculus, along with prereqs like English and history. On top of this, I needed to take not the average five classes a semester (which was considered to be a ‘full load’), but six. Six classes a semester. And since I had to be at the Hecht Center every day for practice at 2:45 (to get taped and meetings), my classes would be starting 915am five days a week.

Early on in my life I discovered that I’m a night person. When I was nine I would stay up till the Monday Night game was 100% finished if it were a blowout. That would often be 12:30am. I had a TV room that was pretty much all mine and my mother let me stay up without question. Both my parents are late-night people so they understood me. Was it the healthiest thing in the world staying up past midnight on a school night? No, but I did it and I would've just laid in bed tossing and turning anyway. Elementary school didn’t start till 930am, but middle and high school were 825am. I was always late. Waking up in the morning was a daily hell. Missing school was thus one of my favorite things in the world since it meant I could sleep in. I faked being sick more than most kids for the extra sleep and late morning 80s gameshows like the Price Is Right, Card Sharks, and Press Your Luck. I really just wanted the space to move at my own pace. If school started 11am, I wouldn’t have ever missed a day.

College was supposed to be my time to make my own schedule. No more mom waking me up in the morning and me begging for five more minutes. I’d sleep till 10 or 11am.. That was my goal.

But if I wanted to be in the AE program I’d have to alter my sleep-late dreams.

My roommate came back. He was a goofy guy named Mike from Rhode Island who wore wire-rim glasses, laid around in his too-big tighty-whities, looked like Jon Lovetts and did a good Jonny Carson impression.

He loved Andrew Dice Clay and Ford Fairlane was his favorite movie. We got along great. Him, me, and the Aussies were a little gang. I drove them all over Miami.

School started, and after just a week of dealing with the early schedule and the impossible classes where I sat totally clueless, I went to my adviser and told him that the AE program just wasn’t for me. I entered the Arts & Sciences department, dropped all the hard early classes, cut down to 12 credits and only took core curriculum. I got my late wake up, and on Fridays I cut class, giving myself a long weekend every weekend.

The first few weeks of school are a blur. I hardly went to class. I drank almost every night, and Thursday, Friday, and Saturday nights were benders. I had a fake ID (not that medical emergency card, but a well-done fake NJ drivers license) and my new friends were 21.

Coconut Grove was the place to be. There was a huge mostly outdoor bar called Señor Frogs where everyone went on Thursdays. I was having a great time.

For some reason I decided to pledge a fraternity. Though I liked my new friends, the Aussies were only at Miami for a few more months, and Mike was pretty sure this would be his last semester at UM. I needed a crew, needed a bigger group of friends so I pledged Pi Kappa Alpha. Pike was full of meatheads. They reminded me a lot of some friends from SHS and in fact most were from the Tri-State area. They had a frat house with a pool that was 10 years past needing to be condemned. I made friends with one of my pledge bothers. His name was Ricky (not his real name and later you’ll know why), a Cuban-American from northern NJ. We fast became best friends.

On the night we got our ‘big brothers’ I was served a drink called ‘Skip And Go Naked’. Maybe ten kinds of alcohol mixed with Country Time lemonade, beer, margarita mix and who knows what else. I was a sloppy mess on the dance floor, grinding to Dubby Reggae, got kicked out of two bars, almost started three fights and came super close to being arrested.

That night, trying to survive bedspins and only a little bit conscious, a neighbor came into my room. She and I had hung out as totally just friends. She wasn’t my type. She started taking advantage of me; kissed me, tried pulling down my pants, straddled me. I leaned over and puked into a garbage can. She tried to kiss me again. I had to fight her off. She wouldn’t take ‘no’ for an answer and wasn’t a small girl. I had to heave her off of me. Then I stumbled to the bathroom to hug the porcelain god for an hour. When I came back to my bed she was gone.

A week later after a frat party, Ricky, myself, and two freshman girls went to South Beach. One of the girls had a brand new Dodge Stealth. She made the first move as we lay on the dunes. We fooled around a little and ended up sleeping in the same bed later that night. The next day, at lunch with a bunch of the brothers, to sound like a big shot, I told one of them what Ricky and I did the night before.

You fooled around with who?

I told him the girl’s name again.

That girl was a big crush of one of the most popular brothers, a big Puerto Rican kid. Although they didn’t have any kind of romantic action going on, he was majorly hot for her even though she just saw him as a friend. He lost it. Ordered me to stop seeing her. Yeah, okay.

The girl called me constantly to come hang out. I couldn’t stay away. I hadn’t been with a girl in many months. I was desperate and now that the seal was broken and I knew she liked me, I wasn’t so shy. The frat brother called her so much it was stalking. He would show up at her dorm room at all hours unannounced. He caught me there. Went ballistic. He was a huge fat kid and tried to intimate me. When that didn’t work he told me I’d get ‘black-balled’…aka kicked out of the pledge class. I left her room only because if I didn’t there would’ve been a fight. I was back the next night, though. And the one after that. The girl and I were just fooling around, nothing too intense. In her CD player was always Pearl Jam’s TEN or The Chili Peppers Blood Sugar Sex Magic. No more than three weeks after pledging, and reusing to stop hanging out with the girl, a meeting was called to determine my fate. They led me into the common room with the whole fraternity there. I wore my tie as a blindfold. For ten minutes I stood there listening to the forlorn brother who’s crush I was stealing tell me how I wasn’t brother material and if I wanted to stay, I’d have to never see the girl again.

He demanded an answer, but I just stood there. I didn’t care if they kicked me out, and I wasn’t going to fold for that chump. There was a time in that room when I thought that shitbag brother might try to get everyone to jump me, but there were also a few guys in there who really liked me.

After the grilling, they lined the pledge class up and told everyone I had been black-balled.

Fine, see ya. I couldn’t care less. A week later Ricky quit the frat. We spent all our time together. A lot of daytime pot smoking and playing RISK on his green-screened Mac.

When it came to school, I cut about half my classes. By the fifth week of school I still didn’t even have a text book for one of my classes. I tried cramming for a math test at the beach. Then partied too hard later that night. During the test I had to leave to throw up several times. I got a 34% on the test. And please don’t think I’m glorifying being a total joke when it came to school work. Doing good at school isn’t that hard. My problem was that I was never taught how to study. This vital component had been overlooked. It wasn’t until my senior year of college and with the help of a very smart girlfriend that I learned how to really study. After that I was a B+ student with lots of A’s in there. In high school, I thought the kids who did so good had something more than me. I felt I was as smart as them, but just lacking some extra gear. The only difference was that I lacked the ability to organize and study. That was it. No magic there.

Attending Biology 101 one day, which I had only been to twice, I remember being so lost that I got up and left. No way I’d be passing that class so I dropped it, but it was past the time when you could drop without getting an ‘I’ or ‘Incomplete’ which was some kind of ugly purgatory grade that affected your GPA negatively.

But I was having a hell of a good time. Miami was a strange and beautiful new world for me. I learned my way driving around the city and spent a lot of time going to the beach and investigating many of the city’s nooks and crannies alone. I worked out at a gym across from campus and snuck onto the football practice fields at night to run sprints. Winter was non-existent for the first time in my life. I played tons of ‘Sonic The Hedgehog’ while listening to The Stone’s Let It Bleed on continuous repeat. (I almost murdered my roommate one night when I found out he shutdown the SEGA, which had a paused almost-completed Sonic game on it. Yeah, I was a Sonic addict.)

A few days before the running test on the 25th of February, I started to get nervous. Everyone back at home knew I had gone to Miami. There were even kids from rival schools who talked about me going to Miami. While I don’t think anyone was thinking I was going to make some big impact on the team, they thought at least I’d make it. If I failed, going back to Scarsdale would’ve been hard. Having the deli guy ask me how football was going and having to tell him I wasn’t playing? Nah, I couldn't have that.

The night before the test, I pulled out a bottle of pills. In the bottle were bronchilators; aka ‘Truckers Speed’. Pure ephedrine. Outlawed since the mid ‘90s (today you can find pills with ephedra, which is an herbal extract, but that is nowhere near the same thing as ephedrine). I bought the bottle over a year before at East Coast Fitness. Weightlifters liked to take them. I was told they’d be good for football. After the caffeine pill debacle, I never even considered taking the speed pills.

In an act of pure nearly fatal stupidity, I decide that tomorrow for the running test I will take two pills.

I wake up 615am. It’s a misty and cool morning. The football complex is a short seven minute walk from my dorm. I take my time. We have to be there 7am. I’m soaking it all in. This is a big moment in my life. Before I leave the dorm, I pop two pills and swallow them on an empty stomach. At the football fields, I find about 35 guys there for the tryout. Some look like legit football players, some not. We check in, step on a scale, and began a team stretch on the 50-yard Astroturf field. A lot of the guys are gripping about being up so early. I can’t believe it. This is the Miami Hurricanes, how could they be complaining?

Greentree practice fields and Hecht Athletic Center @UM

Out with us is Coach Role, along with an Assistant Strength coach, two Graduate Assistants including Greg Mark, and the Special Teams coach. Not one of them wants to be there. The mist lifts but it remains a rare gray day. Soon we are led to the field and given the rundown by Role.

I don’t know why any of you are out here, growls Role. You ain’t players. If you were, you’d be here already. We don’t need you. Probably ain’t none of you makin’ the team anyway, but we gotta do this.

Then he tells us about the run test: 16x100-yard sprints. You have 18-seconds to run ‘em and a 35-second rest between runs.

Oh…shit, I didn’t know they’d be timed like this.

The anti-pep talk Role gives us hits home. In my mind I’m already preparing what I will tell people when I don’t make the team. Role’s speech really got into my head, but not as badly as the ten guys who just pack up and leave before even running a yard.

Right about now, the ephedrine is kicking in, hard. As we line up for the first sprint, my heart pounding, I realize I’ve made a HUGE mistake. Haven’t learned a damn thing from my caffeine pill experience. This is how people die.

The first seven sprints go pretty good. We were all making time. I’m always in the first group to finish and start to think that I actually made a smart choice taking the pills. By the 8th sprint, some of the bigger guys have dropped out. By the 9th sprint, I enter an alternate reality and am in trouble.

As we run the 10th sprint, my legs turn into cement-filled meatbags. My entire body is ceasing up, but boy, I tell you, my lungs are sucking in that air like never before. I’m hot, panting, heart thudding, head throbbing.

11th sprint and I just make it in 18 seconds. Guys are collapsing in the end zone and not making it up to the line in 35 seconds. My heart-rate is off the chart. The 35-seconds between sprints isn’t enough time for me to catch even a second of breath, but next thing I know, moving on sheer willpower, I’m in a 3-point-stance on the line ready to run the 12th sprint. I lumber down the field. Thighs full of crumbled concrete and on fire. Sounds are warped. Having a partial out-of-body experience. I make it the 100 yards by the nick of time. My low-center of gravity makes it very hard for me to fall over. I stagger around the end zone but I am not going to quit. Not a chance. Only 4 more and I make the team.

Thankfully, someone else makes that call for me.

The Special Teams coach grabs my arm, looks me in the eyes. By this time I have severe tunnel-vision. I try to break his grasp. I only have a few seconds to get up to the line. He’s ruining my chance. No, I have to go on.

You’re done, he says. That’s it. I don’t have the strength to break his grip.

I think maybe he saved my life.

Stumbling to the Astroturf field, I finally go to the ground, my hopes and dreams dashed. One of the coaches comes up and asks if I’m okay. I mumble something and that’s good enough for him.

I lay there for an hour at least, totally unable to move more than a wiggle. No one came out to check on me. Surely someone must’ve seen this big body laying there for so long. Slowly I came back from the abyss, take a shower in the empty locker-room, and shuffle back to the dorm. I sleep till mid-afternoon.

The next day, certain I was not going to make the team, I go talk to Coach Mark. My plan is to lobby him, convince him not to judge me by the running test. I can play ball. I’m not a chump like most of the guys out there. I’ll be an asset to the team. Above all, coach, I’m not ready to stop playing football.

Mark said: Yeah, well, I wasn’t ready to stop playing either, but when I got cut by the Eagles, my career was over.

My heart sank even further.

But, he said, perhaps sensing my suffering and seeing my desperate long face, Coach Erickson likes having big bodies around to beat up, it’s all up to him. He might make an exception in your case, who knows. Check my door on Friday 2pm to see if you made it.

All was not lost.

The next day and a half were excruciating.

On Friday at 2pm I rushed over to the football offices. Walking up to that door was a feeling of anticipation I cannot even describe. There were 6 names on the list. I was one of them. I’d done it, I made the Miami Hurricanes football team. Big bodies to beat up. I would be a tacking dummy. No problem. I was honored. Below the list of names was a note saying to be at the lockerroom 2pm sharp on March 15, the day before spring football started.

First person I called was my mom. The next week were midterms (which I blew off) and then everyone was off on Spring Break. I was on top of the world.

10

Going to school at Miami is like a permanent Spring Break, though, there was Key West, a MAJOR spring break destination for FL colleges and other Southern universities. Ricky and I drove down. We stayed with two girls we knew and ten other people in a hotel room. One of them had a boyfriend with her, who, ironically, attended the Naval Academy. That girl juggled me as her side-piece. In the middle of the night she would lay down with me on the floor and we’d fool around. She made all the moves. Key West was wild and crazy; a mini Cancun. I’d never experienced anything like it. Sex, drugs, drinking, music. There were no rules. Anything goes.

Ricky and I didn’t stay the whole week. We came back to the dorms after five days and were greeted with terrible news. A bunch of guys from Ricky’s floor had been in an accident in Cancun. Their jeep had crashed. One kid was dead, the other terribly burned. We all used to hang out in Ricky’s room playing RISK and smoking weed.

March 15th I was 20 minutes early for our football orientation. A tanned and rested Coach Mark started off by introducing the new walk-ons to the equipment managers who would be giving us our lockers and equipment.

People who haven’t been around a major college program or an NFL team have no idea what it takes to run the organization. There are hundreds of people, from secretaries, to semi-retired state troopers acting as motorcade escorts, to trainers, and of course, the equipment guys. They are out on the field hours before every practice, during, and hours later putting back all the equipment. There must’ve been two-dozen of them who worked the field. Their home was just beyond the locker room buried deep within the Hecht Center, behind powder-coated metal grating—a dreary dungeon with no windows and ten industrial laundry machines. The core group of equipment guys (not student helpers) who did this for a living seemed to hang out there 20 hours a day.

The head Equipment Manager was a wild-eyed maniac. The four guys directly under him were flat out assholes to all us walk-ons. The second in command, a four-foot-nine, stocky tiny guy named Bobby, took great sadisitic joy in messing with us. He thought he was some kind of demigod because he held Erickson’s wires during a game (this was the era before wireless comms, meaning the head coach’s headset had wires connected to it and someone had to shadow the coach, keep slack, and make sure the cords didn’t get tangled).

Bobby gave us the worst shoulder pads in the inventory. The Bike brand helmet was old and the inflatable air cushion inside had a hole in it, the pants were old and smelly. As for cleats we were given a bin to fish a pair out of. I asked for a cup. What’s that? asked Bobby. I told him it protects your balls. It was like he had never heard of one. Finally he sort of understood. No one wears those. Just use the jock. For me, a cup was the third most important piece of equipment behind helmet and shoulder pads. How could these guys not wear them? I found out later that the bulky plastic cup hindered speed, and no one wanted to reduce their most valuable asset, even if it meant getting their nuts crushed.

Another important piece of equipment I had to do without was a mouthpiece. Everyone but the walk-ons had professionally molded orange mouthpieces. It took six days for Bobby to get me a cheap one you could buy at a sporting goods store, and since I didn’t have access to boiling water to mold it, the gummy mouthguard was useless. (This being before the age of Dick’s and having no idea where the closest little sporting supply store was, I couldn’t get one myself.)

The locker-room was now full of football players. I moved unnoticed among them. Didn’t talk to anyone. This was going to be very different than high school.

First day of Spring ball I walked out onto the giant practice fields like filled with confident apprehension. I knew one guy on the team. Guido was his name. We had a lot in common and I really liked him. Our lockers were also right next to each other. A bunch of us walk-ons mingled together while team veterans were all fun n’ games. When getting my equipment the day before, the equipment guys asked me if I was on offense or defense. I could literally pick what I wanted to play. For a brief second I considered choosing offense. Maybe I could become an offensive guard, or…a fullback!

Defense, I said, and received an orange practice jersey (#90) instead of a white one (offense). The jersey was 10 years old.

The team was split between offense and defense. Even during stretching we were separated with the captains in between (who were a rotating group of soon-to-be seniors).

This was the first practice for the reigning National Championship team. There was a great amount of energy and excitement in the air. The team was stacked. Many were saying it would be even better than previous year. This was another UM dynasty in the making and suddenly I was right in the middle of it.

After stretching, I was lost as everyone ran to their position coaches. On a whim, I went with the linebackers (LBs). Coach Tuberville was LB coach AND 1st assistant defensive coordinator. He was a straight-talkin’ honest man with a strong southern twang. About 12 LBs were out there just throwing footballs around. I ended up having a catch with a player named Kevin. He was a white kid from NY too, but upstate near Buffalo. Movie-star hair, good-looking, short but built, Kevin had the prototypical Division-1 football body: Wide shoulders, barrel-chested, thick hips, flat stomach, and skinny calves into skinny ankles.

Talking to another player mid pass who had asked who I was, Kevin said: I have no idea.

“Alexi,” I said.

And thus began the butchering of my name. I never cared of course, but I would become known as Lexus Mercedes. Coach Role called me Ali Mertoz. Coach Tuberville stopped trying and just called me Alex. Everyone was pretty cool and accepting. We ran drills. I felt good on my feet. Nothing was overwhelming. The hitting was hard but restrained. The heat was something new; that South FL sun beating down on us made hydration a must.

At SHS we had to ask permission to drink water and had designated water breaks—a horrendous 1950s policy. At UM there were these handcarts powered by a car battery and eight hoses spouting from a five-gallon cooler. You’d just hold down a lever and water shot into your mouth. I thought the system was brilliant. Even better, two water carts had Gatorade in them!

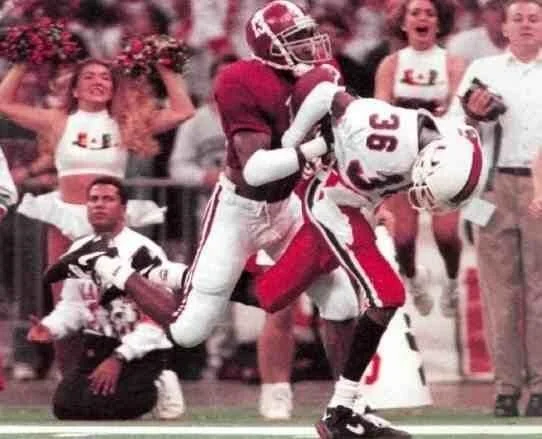

Armstead, Barrow, and Smith

The starting three linebackers from the previous season were returning: Darren Smith, Jessie Armstead, and middle LB Michael Barrow who was also the team leader. Hands down the greatest linebacking threesome in NCAA history. All of these guys would go on to have great NFL careers. I was the heaviest LB out there, outweighing some of the guys by 15lbs. We were all also around the same height. They were all much faster than me, but quickness in a small space was surprisingly relatively equal. I was as strong as any of them, and when it came to hitting, I was 100% on their level. What I’m getting at, is that I wasn’t overmatched, I wasn’t Rudy. In many ways I was very surprised, and at the same time I’m not claiming I was on the same level as those around me, just not overwhelmed by the great talent. I could hang with these guys, there was no doubt, and that was a huge victory in itself.

We ran this one drill where you stood in-between two guys. One five-yards to your left, one five to your right, and Coach Tuberville threw a ball to one of those guys and you had to beat the pass and knock it down. On my second time doing the drill I batted the ball. Quickness, fast-reaction, no problem.

Another drill was a team defensive drill where the walk-ons played ‘rabbit’. The rabbit catches a swing pass and runs down the sidelines while the entire defense tries to get a hand on you. Instead of a JackRabbit, I was more like one of those floppy Easter bunnies, aka kinda SLOW. Everyone got their hand on me. Some guys punched me in the gut when they ran by. I didn’t mind. Some tried punching in the nuts. That I did mind. Later in the practice there were some light 7-on-7 drills (meaning everyone but linemen). I stood there on the sidelines soaking it all it. A long weird road it had been to get to this moment and I absolutely had no idea where it would go. It didn’t matter, I was there and it was a huge personal triumph.

Practice was, dare I say, easy? Even the running at the end wasn’t a big deal. Just a bunch of 52-yard sprints across the field’s width. I could do this.

Next couple of practices were much the same. For long swaths of them I stood there watching with a smile on my face. The smell of the freshly cut Bermuda grass imprinted onto my DNA (grounds crew cut the grass every day to make sure it was super short which made for a fast surface. The longer the grass, the slower the surface).

I learned that the biggest difference between high school and college football (besides the obvious talent level) was that in high school only about a 1/3rd of the guys really want to go at it in the pit. I mean really craved it. The rest might like the game and even be good at it, but they aren’t starved for the contact. In college…everyone is starved. Everyone hits big.

I studied the UM football guide inside and out. I knew every player and their background. There was one defensive lineman who I approached and enjoyed talking to before practice. He had a father I knew very well from my youth. The father’s name was Rocky Johnson, the son’s name…Dwayne Johnson, later to be known as ‘The Rock’ and known on the team as ‘Dewey’.

Dewey

In the guide, I found out a relative of Dwayne’s was Jimmy ‘SuperFly’ Snuka, my favorite wrestler from the early ‘80s. Dwayne was a quiet guy and entertained my questions and ramblings. I would chat him up before practice nearly every day. We talked about how interesting and amazing it was that people from the South Pacific islands of Samoa and Tonga were such good football players. Dwayne said it was because of their proud warrior culture and the fact they were big, strong, and natural athletes.

A player who you DIDN’T want to talk to was future NFL Hall of Famer Warren Sapp. Sapp had the energy of 1000 Energizer Rabbits. His motor never idled during practice or in the weight or lockerroom. Always jawing and playing practical jokes, he was keen on stealing people’s helmets and hiding them.

The last thing you wanted to do was line up for team stretch and not have a helmet on. He would even rip the helmet out of guys hands and run with it. The whole team would hoot and holler. I saw him throw a few helmets over the fence into a canal. It happened to a walk-on. He chased Sapp around until Sapp stopped and just leveled the kid with a shoulder block, then he tossed the helmet over the fence. That walk-on became very sparse after the incident. Sapp wasn’t a bad guy, and he always had a smile on his face, he just liked to mess with people. You couldn’t really be mad at the guy, but you didn’t want his attention. Ten months down the road, I got his attention.

Sapp catching Charlie Ward

Then there was a player with another famous father. When I first saw him, I thought I’d seen a ghost. There sitting at his locker was Bob Marley, except with short hair. His name was Rohan Marley, an LB. We’d smack heads many times in the year to come.

Rohan Marley

The easy practices ended on Thursday.

Walking out to the field before stretching, I’m met by hundreds of coaches. Small college and high school coaches from around the nation have descended on UM for a weekend-long coaches clinic. The visiting coaches study our stretching as if there’s gonna be a test later. Maybe there will be, who knows.

Right after stretching I hear the words ‘COVERAGE DRILL!’ Players start getting excited. We were finally going to do some full-speed hitting, and take a wild guess who the tackling dummies were gonna be?

The University of Miami is a private university. This means it’s more expensive than a public university like FSU. A team like FSU could have 40+ walk-ons. Ohio State 40+. At UM for Spring ball, there were roughly 15 of us (new guys and veteran walk-ons). Out the 15, I’d say seven failed to show up on a regular basis (and no one cared or took notice). Of the remaining 7, only about 4 of us actually contributed anything. The others just stood around. Some guys were just way too small. How they made the team I had no idea, but I heard some suspicious things, like it was a favor and that kind of stuff.

Any drill where there’s going to be some serious head knocking would be a ticket to the hospital for these smaller guys. (Suspiciously, a few of walk-ons who showed up on a regular basis were absent this day as if they’d been forewarned and knew to stay away.)

Coverage Drill.

I got curious when two of the veteran walk-ons rushed to go pick up two hand-held padded shields (which meant they weren’t going to get tackled), leaving six of us to be the tackling dummies for almost the entire Hurricanes football team! (QBs and most first-string players would not be taking part.)

The drill goes like this: It’s meant to simulate coverage on a kickoff, so 55 guys line up 52-yards away. They are to sprint 35 yards full speed and hit the guys with the shields while losing little velocity, go another 10-yards where they will reach a standing dummy. Simultaneously as the player reaches the dummy, the ball carrier (walk on) is told to go left or right. The attacking player makes a quick cut without losing any steam, and full-speed tackles the ball carrier after a 15 yard sprint.

Lined up were all the visiting coaches and players who were sitting out the drill. Evidently, this drill had been a highlight at UM for many years and everyone was pumped. I now knew what those small younger kids at SHS must’ve felt like when they faced their first live hitting with the seniors.

By this practice I had started wearing my huge shoulder pads from high school. With the neck roll I looked like a tank. I had a lot of muscle and weight on me. A 250-pound ball-carrier is never anyone’s favorite person to tackle. Before the drill commenced, I promised myself I would make people pay for hitting me.

To the great disappointment of the large crowd, the first two ball carriers dove to the ground before getting hit. I can’t blame them. You’re a walk on, you have nothing to gain. You’re 5-9 160lbs. You shouldn’t even be there in the first place.

My turn comes. I can hear the crowd get excited. They know there is going to be a big hit.

They’re right.

I trot out there with ball tucked into my side, am told to run right, and sprint for an orange cone. The player’s name bearing down on me is Denovan, a tall defensive end. Now, for the record, though I dreamed of being a fullback, I had never received any real coaching as how to run with the football. I run practically straight up…not the way it’s done.

CRUNCH.

A moment before impact, I lowered my head a little as Denovan planted the crown of his helmet into my left earhole. We went down in a heap. A very hard hit, and the crowd ‘ooowed’, but thankfully it wasn’t a concussion kind of hit, though my jaw did feel out of place. I wasn’t wearing a mouthpiece. I’m lucky I didn’t lose a tooth. No doubt there would be some serious bruising behind my ear.

It felt good to be hitting again. I just wished I could be doing the tackling.

Again we cycled to the two small guys, and again they took a dive. This time the coaches went crazy. They grabbed each guy and tossed them to the side and told them to get the hell out of there. The crowd was aching for a hit. My turn came up. A coach slammed the ball into my stomach and yelled at me to go left, hard.

I saw Rohan Marley sprinting down the field. Unlike his father, Rohan was built like a fire hydrant. 5-8 on a tall day and packed with 225lbs of muscle, Rohan could bring the pain. He made his cut. I yelled a battle cry as we made contact. I hit him harder than probably anyone in my life. I just trucked right over him but my momentum took me to the ground. The crowd went wild. I spiked the football. Rohan popped up like nothing happened. Showing that a hit hurt was one of the biggest taboos at Miami. In my time there, after the hardest hits, time and time again, guys would pop up and be pretend to be ok.

By now there were just a few of us running. There was hardly any time between hits to catch your breath. Before my third run, a junior RB named Donnel Bennet left the line of coaches and players to give me 20-seconds of coaching on how to run with the ball.

Lower your goddam pads!

Meaning, don’t run like Fred Fucking Flintstone!

The hits got harder and harder. So hard, in fact, I do not remember the four runs before my last run.

All in all I was feeling pretty good. My shoulder hurt, and my head would have contusions all over it, but it wasn’t like I was in a concussion dream world.

That last run I would be going up against the LB Kevin. It would be the hardest hit of the day and the last run of the day.

Low shoulders. Explode through the hit. Keep pumping your legs. Head up so you can see where you’re going. Those were the tips Bennet gave me. I thought he would make a great coach (I recently found out he is Head Coach of a South FL high school football powerhouse).

Kevin came charging down field. He was stout and fast. I went left. Seconds before impact I yelled again; a gargled battle cry. We contacted and down Kevin went. I officially ran him over, putting him square on his ass, but as I trucked over him, he yanked on my jersey and I stumbled, couldn’t keep my feet. At Miami, and I’m sure at almost all big football programs, how hard you hit is how you gain respect. As a walk on, hard-hitting was all I had to cling to. If I couldn’t hit, I had nothing.

Suddenly the the drill ended with a loud horn noise. Practice was moved along by a big digital clock that made an annoying sound when it was time to move to the next evolution. Defense moved on to rabbit pursuit. I stepped up to run, but Coach Mark told me they wanted this to look good for the cameras (which were filming practice from an elevated platform). Good, I needed a break.

Later during practice I was involved in another tackling drill. This time with just the defensive linemen going against offensive linemen. Again we were surrounded by some of the visiting coaches, but this wasn’t a team drill so there was less attention. The first time I ran, I hit a defensive tackle named Pat Riley. He was 6-4 and a solid 280. The collision was full speed with my head down. Hard hit. Okay, no problem. As Riley was getting off me, he told me I better slow it down or I’d get my ass kicked. I understood. It was just a drill, no need to blow it up. I’d said the same thing over the years at SHS to many a younger kid being what we called a ‘half-speed All-American’. It meant that while the starters were going half-speed, the scout team guy was going full. I hated when kids did that, and now that’s exactly what I was doing. The problem was at Miami the guys hitting you weren’t going half speed, and there’s a coach at your back demanding that you go full-speed. What to do?

You listen to your teammates, that’s what you do.

There were some solid collisions during that drill, but nothing to get excited about. After all positions drills were done, the first 11-on-11 mini scrimmage happened. It was my first look at full-speed game-situation play. I was amazed. The speed was unlike anything I’d ever seen before. And the passes? 60 yard strikes. Amazing corner-back vs wide receiver battles. Hard running back vs. linebacker hits. This was a great football team with talent everywhere.

After that practice I signed my first autograph. They’d let a bunch of kids through the fence. Not one of them cared that I was just a walk-on. I must’ve scribbled my name ten times.

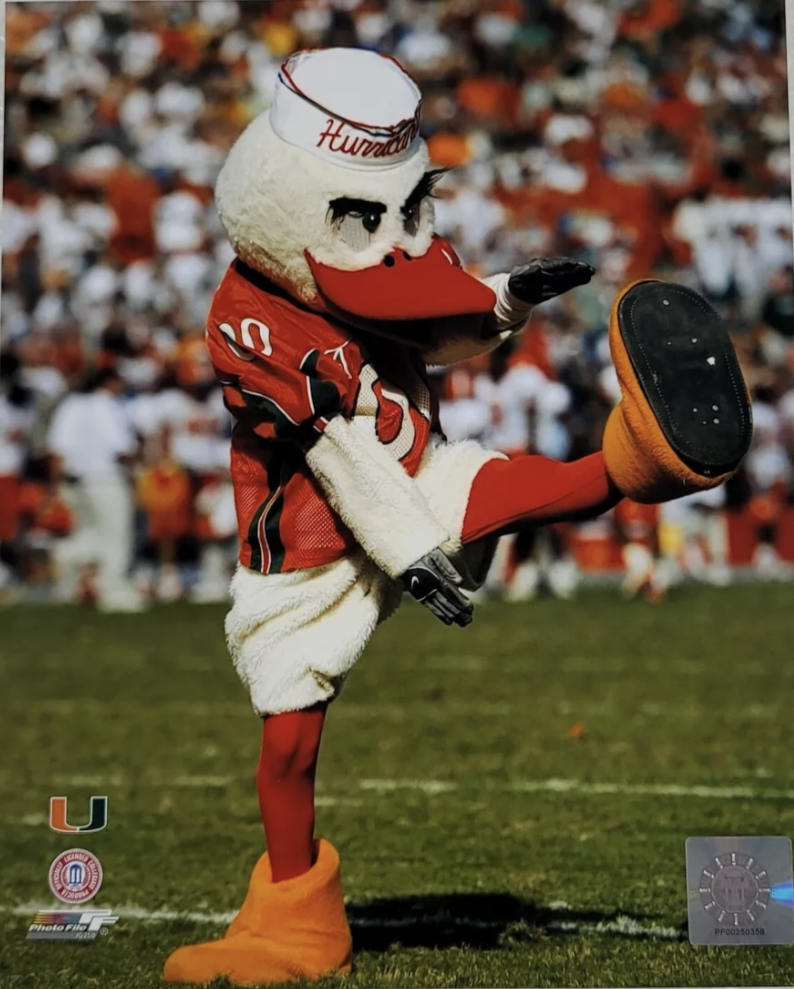

I decided to work out after practice. The UM gym hadn’t been updated since the late 70s. It had new equipment, but was a windowless cave right off the football fields. The walls were concrete painted orange and black with encouraging slogans painted in big ‘Impact’ font. Every wall had an ibis caricature painted on it. The ibis is the UM mascot. Besides the Oregon Ducks, I can’t readily think of a less fearful mascot in college sports. Actually, since 97.8% of people don’t even know what an ibis is, it’s probably the least fear inducing.

Why the ibis? The ibis is the last bird or animal to be seen right before a hurricane hits. No one knows why they aren’t afraid of canes. (Years after my football days, I watched a video that my sister filmed during Hurricane Wilma of a flock of ibis riding out the Cat-4 storm along a canal. When the wind gusted up to 150mph, the funny white birds with long orange beaks and orange legs would roll with the wind, then pop up and find their footing against the gale.) The lowly ibis also happens to be a sacred bird in Ancient Egypt, and one of the most important figures in their pantheon is an ibis-headed god named Thoth. I would tell people about this fact when trying to up-sell our mascot.

That raw, dark gym screamed gritty football. No frills. Miami might've been all about swagger and showtime, but truth was most of the guys on the team were from Miami and came from tough inner-city neighborhoods on par with anything the Bronx or Compton could dish out. That team was rough and gutsy, but like the City of Miami, there was a never-dimming, mischievous shimmer to the program, like the toothy, spirited grin and gleaming eyes of the Cheshire Cat. A cunning. A knowing. Intelligence and danger.

Sebastian

The gym wasn’t only for the football team. ALL UM sports teams worked out there. Long and narrow with Coach Rolle’s ‘office’ at the end. On the radio were songs like: I’ve Got A Man; Doo-Doo Brown; Humpty Dance; Back To The Grill Again; and songs by Naughty By Nature, Dre & Snoop. But when the county guys on the team were in there alone, there’d be a Country station on. New Rock&Roll was the agreed upon medium everyone could deal with and luckily that was Rolle’s favorite kind of music.

Going back to the lockerroom, I pass a fellow walk-on, a veteran. His face is bright red—eyes bloodshot and watery. He’s kinda smiling, but then again, this guy is always kinda smiling.

“They fucking spanked me,” he coughed.

Thankfully for everyone, that stupid ritual never happened to me. My whole time on the team I only saw the aftermath of it twice, but I heard a firsthand, detailed account of Gang Spanking: a dozen or more guys lined up as other guys held the victim over the back of a couch. Often it happened after a shower so the victim would be naked. Embossed on his ass would be multiple Adidas leafs as that was what was on the sole of the Adidas thong sandal they gave everyone except walk-ons. Coaches didn’t venture that often into the 4000sqf lockerroom. It was run by the team. Every day, I mean every.single.day someone would ‘try’ someone else and next thing you know two guys are wrestling, being thrown over couches, slammed into lockers. Sometimes it’d be a group brawl. Punches were rare. This was about your ability to beat someone with your strength and quickness. I must’ve given off an aura of some sort, what the black guys called ‘crazy white dude vibe’, because I was only ‘tried’ once.

That night hanging out in the dorms, I proudly showed off my wounds. My left ear had been bloodied and now had a thin crimson crust on it. The skull behind the ear was swollen and purple. My jaw clicked. My right forearm, which I hadn’t felt till later, had the imprint of a face mask embossed into it. I was limping. Why football players enjoy the after-affects of a hard practice or game isn’t easily summed up with words. I think it’s due to some deep biological hunter imprint. Like a hard days’ physical work, even if it’s nearly backbreaking, just feels good when you’re sitting there on the couch after a hot shower. You might ache all over, but dammit, you feel alive.

The second week of Spring ball the team’s long snapper named Tom comes up to me.

‘Snapping is a good way to contribute and get a scholarship,’ he says. It had worked for him. Going into his senior season, Tom had finally won a full ride.

While I didn’t scoff at the idea, I wasn’t gung-ho about it either. Long snapper? The single most unheralded person on the field at any level. The only time anyone ever noticed the snapper was when they sent the ball five yards over the punter’s head and cost the team a victory. On top of that, legs wide as could be, looking between them at whoever you were snapping to, left you totally defenseless. Every time you snapped, you’d get your ass planted into the turf. I did it all the time in high school. Paradoxically, on punts, some teams didn’t even touch the snapper, letting him run down field unabated, showing total lack of respect for him as a player. At the same time, every team needs a good and super-reliable long snapper. Tom taught me the technique. You used two hands and torqued the ball. Tom could launch it back like a missile. Mine tended to roll. My shoulder pads were too big to do it, but when I really tried I could get the ball back there at decent speed. It was something I would consider working on but with little enthusiasm.

The rest of Spring practice was over before I knew it. The final day would be an inter-team scrimmage known as The Spring Game. Nowadays, at major colleges all over the nation, The Spring Game has become a huge deal. Ohio State averages 100,000 at their game and a party atmosphere. The most UM offered back then was an open gate where maybe a thousand people came through to watch the scrimmage. Coach Tuberville had taken a liking to me. Not as a player, but as an assistant. Everyday when the starting offense and defense squared off at the end of practice, Tuberville would have me right by his side holding a clipboard and writing down all his defensive calls. I failed to see it then, but this was an amazing opportunity. One of college football’s best defensive minds was giving me access to his inner workings (in one season, Tuberville would become Defensive Coordinator of Miami, then eventually move on to be head coach at Auburn for many successful years, and then a US senator for Alabama), access to his coaching philosophy and secrets. That kind of access you can’t buy. This could lead to something, maybe me becoming a coach. But, like the long snapping idea, I wasn’t into it. Not my destiny.

For the scrimmage, I asked Tuberville if I would be getting a chance to play. He said everyone played. That wasn’t true. I stood there plastered to Tuberville’s side for three hours. He wouldn’t even let me wear my helmet. As the scrimmage went on and the 4th-string guys were in there playing, I realized I wouldn’t be getting any time. I thought over the past two weeks that I’d proven I could hang with anyone on the football field. It wasn’t like I would go out there and get hurt. Even twice during practice I’d played middle LB, calling plays and everything. I’d made tackles in an 11-on-11 situation. I even covered a few passplays well. All I wanted to do was play. I wasn’t auditioning or anything like that. I had no illusions of grader. Just give me some playing time.

As the last plays of the scrimmage came, I thought about asking to go in. It was a position I had never been in. I hated even thinking about it. Any second I was sure Tuberville would tell me to give him the clipboard, grab my helmet, and get a few plays in. That didn’t happen.

11

The rest of the semester was a complete wash academically. Ricky and I had started hanging out with his brother, Ronnie (also not his real name).

In my life I’ve always gotten along with people like Ronnie. Evil Geniuses. Smart people very in touch with their darkside. Too smart for school, but not too cool. Funny, cunning, weird, master manipulator and highly intelligent, Ronnie lived in a ground floor studio on classy Brickell Avenue near downtown Miami. He talked the biggest game of anyone I had ever met.

Short, stout, overweight, Ronnie assured me he was on his way to big and great things. He had lots of money (he claimed), and though he didn’t have a car (his Ducatti was in the shop…for more than two months) most of his cash was invested in a grow operation in South Miami.

Yes, grow as in he was part of a cannabis grow operation. 250 plants. Pounds of weed grown and sold every three months. Next year Ronnie would be taking over the op. All the profits would be going to him…and Ricky and I if we wanted in.

On Brickell Ave, riding around at night with Ricky’s Jeep top removed, slick streets, it was my own private Miami Vice scene. Ricky, although he liked his brother, warned me all the time that Ronnie was the biggest shit-talker around. The grow op was real, evidently, but who knew if Ronnie would take it over, and if he did, he’d need his own house.

The semester wound down. I only took one final.

Before leaving for the summer I stopped by Mark’s office.

Give me your number and I’ll call you to tell you when to show up for preseason, he said.

A few days after school ended, Zak and Matt, flew down. They’d been sequestered all the way up at the opposite end of the nation in Burlington, VT. We were gonna roadtrip in my 4Runner back to NY, making pit stops in Orlando and New Orleans.

The plan for Orlando was to go to Disney World and eat lots of psychedelic mushrooms. I hadn’t been there since I was seven. We got to the park at 815am, ate 4grms of mushrooms each on empty stomachs and had to borrow a can of warm Coke to wash the fungus down. When I had to buy my ticket, the psyliocibin was hitting my system, signaling the beginning of a 12-hour, truly magical day at Disney World.

…..Yes, it was every bit as fun, amazing and weird as you’d imagine. Rides were breaking down; long lines were journeys into near madness; birds were talking; Mickey’s manifesto was subliminally broadcast through the speakers that were everywhere. On Space Mountain I laughed and cried so hard it was a religious experience. To be back in Mickey Land after so long, and to now be on a psychedelic, was just a beautiful thing.

The three of us Gonzo wannabes next moved on to New Orleans.

One night we visited a strip club. Being extra rowdy at a table was one of the Miami coaches named Ed Orgeron. He coached the defensive line. A wild and loud Cajun, I almost went up to him and told him I was on the team, but he was so crazy I thought it best not to. That evening we were forced to spend the night in the French Quarter as we made a tactical mistake and parked in a garage that closed at 1am. We stayed in a bar populated with people who thought they were vampires. Some of them didn’t seem to be faking it.

That summer Pete and I went to a new gym. I never paid a dime to work out there. I literately just walked in every day, said ‘hi’ to the girl at the front desk and that was it. With my orange-covered workout manual from UM, I followed the eight-week conditioning program the best I could. Another important matter was my failing GPA for the semester. With my mother’s help (of course) I got the entire semester expunged. It was taken off the books and I would get a clean slate. I’m not proud of it, but that’s the truth of what happened.

Back then I didn’t feel personal responsibility for most of my actions. Everything felt like a flowing joke, and in many ways it still does, but part of evolving (I don’t use the term ‘growing up’ because it’s an antiquated idea from the 50s, like only letting your players drink water at practice during scheduled water breaks) is learning to be responsible and take ownership of what you do. When I was 19-20 I didn’t care. Now, I do. Being an irresponsible kid is just part of life and I think it’s important not to beat ourselves up too much over this fact. That doesn’t mean just because we’re 19 we can be terrible people, it means it’s called a ‘lifetime’ for a reason. We don’t have to have it all figured out by 24. In fact, we may never get ‘it’ figured out and that’s totally okay. I consider myself blessed to always be out of phase-shift with the mainstream experience. It’s not something I cultivate, it’s just how my life is and I’m totally at peace with it. Now, when it comes to procrastinating, that’s an affliction I think we have to cure, or end up not getting as much out of life as life wants us to get.

During July a near tragedy almost happens. Nick Bogaty has a small party at his house. 30 people show up, no big deal. A bunch of us are in his attic playing Tecmo Bowl (which to this day I contend IS THE BEST console football game of all time) when someone comes running up the stairs.

“Guys, there’s a fight!”

It went down like this: Three girls from another town had come to hang out. The boyfriends of these girls found out and showed up. One of the kids I knew by working out at East Coast, and his father owned a good deli I often visited when in that area. I thought we were friends. He was half anglo, half Philippino. With him were three other guys. One of them was this short kid of Japanese or Vietnamese heritage. I was trying to make peace, but this little fuck was all up in my face, telling me he was going to kick my ass, jabbing his index finger at my nose. I mean he was really going at it. Without warning, using my fast-twitch, I slammed the heel of my right palm into his forehead and exploded through the move. It was more of a push than a punch. The force jacked him five feet backwards into a bush. Everyone laughed and cheered. His friends excavated him from the shrubs and they left. I felt bad. I’d lost my cool. Alone, I walked out to their car and apologized. I looked the kid I knew in the eyes, and honestly said I was out of line and that I was sorry. We shook on it. Even the kid I jacked into the shrubs said all was cool.

It wasn’t.

Twenty minutes later I’m siting in the den watching MTV when I notice a bunch of cars roll up to the house. Not more than a minute later, I hear a commotion in the kitchen on the other side of the house. When I get there, I see one of my good friends bleeding from the head, another is in the kitchen with a face-full of mace.

They’re getting their asses kicked!! yells someone.

There’s a monster inside of me. He is a happy fellow, much more like one of the Wild Things than Godzilla, but he is still a monster. However…when something I care about, or my own well being is threatened, that Wild Thing morphs into a red-eyed banshee. It is as if I’m taken over. (Sometimes I’ve felt like I was born in the wrong age. This world of laws, order, reason, and intellectual pursuits a mere blip in the history of Man, and that a world of chaos, the Samurai, blood, fangs and claws is our true state.)

Next thing I know I grab a 14-inch-long chef knife. It’s one of those expensive, 440-stainless steel ones with a thick shank and artful wooden grip. I charge out the kitchen door and down the steps. Nick follows me, jumps on my back to stop me, rips my shirt off. I am shirtless, barefoot, wearing black army pants and holding a knife Michael Myers would envy.

My mere presence turns the tide of battle.

About seven carloads of idiots have shown up to fight. There are four or five of my friends getting jumped outside and another four inside. When I see another friend bloodied, I fully lose it.

The first car I see is a new white Cadillac, probably the kid’s father’s ride. I stab the trunk, piercing the sheet metal like it were paper. I stab it half a dozen times, then put my fist through one of the back windows using the butt of the knife. I stab the driver’s door repeatedly. Inside are some very terrified kids. I jump on the hood and drop a knee into the metal, denting it severely, yelling my head off, slide off, and come face to face with the kid I jacked into the bushes.

The look on his face I will never forget. It’s the realization he has made a terrible mistake and it might be his last one because I am going to cut his head off. I can only imagine how insane I looked. What was going on in my eyes, what I was saying.

Again I smash the kid in the face and he goes flying backward into a yard. I’m on top of him in a heartbeat, and with the tip of the knife to his chest I growl at him, order them all to leave. Turns out, most of the cars were already speeding away. The kids in the white car are screaming for their little friend to get in. I let him up and tell him if I ever see him again I will blow his brains out with my shotgun.

One wrong move and I could’ve killed that kid. Ruined my life—and of course his—all because he and his friends couldn’t let it go. That is why I called it an ‘almost tragedy’.

You gotta let go.

But, you gotta defend yourself, people who need it, and what is righteous. Those fucking kids betrayed my good nature. We were all lucky to get out of it alive and without long prison terms.

As August arrived, I knew preseason would be starting shortly, but Coach Mark didn’t call and I balked at the idea of calling him. Perhaps file it under ‘wasn’t meant to be’, but when UM preseason started, I was still in NY.

On August 19th, myself and friend since 3rd grade Ben who had redone his senior year of SHS and was going to be my roommate at UM, drove to Miami towing a U-Haul. Even though I had a semester under my belt, it didn’t count academically. Yet, I wasn’t seen as a freshman either. Out of synch again, but Like Jazz, it works for me. Ben had to be there early for orientation. I would join the football team a week late into preseason. I didn’t like this, but I would have five years with the team. I was just getting started.

We got to Miami on August 22nd, and because the dorms weren't open till the next day, we stayed with Ronnie on Brickell Ave. Ben wasn’t exactly happy that I brought him to stay with a “drug dealer”. Taking up the majority of Ronnie’s studio were dozens of foot-and-a-half tall cannabis plants in hydroponic pots. All the gear for the grow system was scattered about. Ronnie had to hand ‘feed’ each plant with a mister. He would draw his blinds and curtains during the day for six hours and illuminate the plants with growlights propped up on bar stools. It was an unholy mess in there, and hot. I saw nothing wrong with the situation, but, in hindsight, maybe it wasn’t the best way for a person to be introduced to their freshman year of college.

And maybe the massive hurricane churning just off the coast threatening to destroy the city probably wasn’t such a good way to begin it either.

Andrew

Out in the Atlantic spun Hurricane Andrew like a buzz-saw. The morning of the 23rd, the entire freshman class was moving into the dorms. A radio played nonstop updates about the impending doom. Late in the morning I broke away from the move and went over to the football complex. The NOAA had just given the almost 100%-certainty that the hurricane would be hitting Miami square in the face in less than 20 hours. The decision had already been made to move the entire football operation 100-miles north to Vero Beach where the LA Dodgers held Spring Training. The program was in evacuation mode. I found Coach Mark. As expected, he was frazzled like everyone else. The season opener was in two weeks, an away night game against Iowa on Sept 5th to be nationally televised. There’d be 90,000 filling the stadium. Iowa was preseason ranked #12, UM #1. It would not be a cakewalk.

The best Mark could offer was for me to just show up at the Vero Beach facility in a few days. We’d see about getting me to join the team then. Back at the dorm frantic parents were moving their children into college under most unique and uncertain circumstances. Danger was in the air.

The University of Miami had been born in 1923…only to be totally leveled three years later by a storm simply known as The Great Miami Hurricane (they didn’t name storms till the 1950s). Once they rebuilt campus, it was decided the new name of sports teams would be…The Hurricanes. Before that, believe it or not, the school sports teams were named after a rotating assortment of local fauna until a suitable one was to be found; like The Bougainvilleas and The Royal Ponicianas. Some of this plant-power is still around, as evidenced by the school’s colors: orange/green/white representing the orange tree and it’s blossoms.

Stanford residential towers

Ben and I didn’t have our parents there freaking out, so we just kicked it and drank beer. As afternoon arrived, word began to spread that the campus would be going into lockdown. It was chaos. No one knew what to do. Were the 14-story towers going to stand up to Andrew’s 195mph gusts? What about food and water? Would the cars be okay? Around 5pm, my friend and I dropped off the U-Haul trailer (the place we dropped it off near Kendall was later wiped off the map). We’d be heading north to West Palm Beach where my father was at his condo and hunker down there.

Like two jackasses, we drive to Miami Beach and look at the darkness coming in from the Atlantic. The Beach was deserted. We drove slowly through the abandoned streets; swirling sky a million shades of grey; 45-knot wind already chugging. On the way west to I-95, a Florida Highway Patrol Officer pulled us over. He read us the riot-act. How stupid are you?! he demanded. Very, was the only right answer.

Night was coming fast and with it stronger winds. Leaving Miami it felt like the storm was right on our tail (and it was). By the time we made it to West Palm 65 miles north, the rain was whipping and wind topped 60 knots. We lost power around 11pm and winds hit 80knots, 75 miles from Andrew’s eye. The tall apartment building swayed and creaked. The sliding glass doors bowed and flexed.

When morning broke, my friend and I were on the road down to Miami. I-95 runs right though the city. It honestly didn’t look so bad…until 95 ended and we hit US-1.

In an epic grace of fortune for the city, Andrew ducked south just before landfall. The dirty, nasty teeth of the north-eastern quadrant (which is the worst part of a hurricane) bored hard into South Miami instead of the main city 15-miles to the north. Places like Homestead and Kendall took the worst beating. As we hit US-1, which I-95 dumps directly into and runs all the way south to the beginning of the Keys, the destruction was massive. Trees were everywhere. Only a narrow path through the six-lane road could be navigated. There was zero, I mean zero police presence. Of course there was no electricity either. Power-lines and snapped poles littered the streets. Every traffic light lay in a heap. Some stores had been looted, others, like Publix were just letting people take pretty much whatever they wanted. Millions were without power. The UM campus had been smashed, but the buildings were still intact even though unsecured dumpsters had been flying around campus all night smashing into buildings.

Word spread fast that school had been canceled for more than two weeks. Everyone had to leave campus immediately. The university was helping people fly out of the city. I visited some girls I knew in an off-campus apartment complex. Steel doors had been bent and ripped off their hinges. Ben got on a flight that night from West Palm.

The next day I went to Dodger Town to check in with the team. It was business as usual on the outside, but inside many players were hurting. At least half the team was from areas severely affected like Homestead. The fates of their families and homes was unknown. I showed up for practice the next day with my shoulder pads ready to take part. Finding me a helmet and pants took some time (unlike during Spring football where all the helmets were white, now I had orange and green stripes on mine, and…the legendary U on each side). I commuted from West Palm to Vero, 40 minutes each way, to practice for seven days straight.

The Miami Hurricanes went on to beat Iowa 24-7 in a very emotional game. Afterwards, the team moved back to campus and I with them, as the dorms had reopened, though not officially. It would still be another week before full campus functions returned. There was a bye between the next opponent and Iowa, so the team had time to lick its wounds. Life was getting back to normal.

12

Scout Team—made up of red-shirt freshmen (scholarship freshmen who would not be playing in games and thus would have five years of eligibility) and walk ons—this little understood and important aspect of football comes with no glory, no greatness, but it’s where young guys learn to play at the college level and make a name for themselves within the team. If you’re really good right out of high school, and you get to preseason and prove you can contribute right away, you go right onto the depth chart, don’t get red-shirted, and never see a minute of scout team. Your eligibility clock starts ticking. Instead of five years, you now only have four. It was pretty rare back then.

Every day during the season, the majority of practice was centered around starting offense and defense running full-on live plays against a scout team defense and offense. When it came to scout defense, we could not hit the QB; and running backs, once they were outside the tackle-box, were not to be bought to the ground (but you could still hit them hard). All the blocking was 100% full-go until the whistle. And the pace of everything was game-speed. I would finally get my taste of what it was like to play on this level.

In the beginning of my time back, I was still doing everything with the LBs, even getting some reps on scout team at the position. After practice one day a particular set of hard conditioning came up. I was not in as good of shape as everyone else. These were 52-yard sprints, touch line, then sprint back the 52-yards…25 of them. We ran them by position on a nonstop cycle. Though I was trying my absolute best, the LBs I ran with all possessed 4.70 speed. (Those tenths of a second bewtwen my 4.95 and their 4.75might not look like a lot, but they mean EVERYTHING in football. A guy running a 4.3 is elite speed. First Round Draft Pick speed. A guy running 5.0+ is never gonna make it unless he’s a 6’5 350lb offensive linemen.) Anyway, it looked like I was dogging it, coming in far last every sprint.

Hey, if you can’t keep up with the LBs run with the linemen!! screamed the toughest guy on the team.

His name: Rusty Medearis.

Rusty Medearis

Rusty played defensive end. At 6-3 and 260 and from the Ozarks, he wasn’t the biggest guy, but he was one of the team leaders, and no one, I mean no one fucked with Rusty (I’m sure when he was a freshman someone did, and paid the price). When he told you to do something, you did it. No questions asked. When Rusty wanted to listen to Garth Brooks in the weight-room, we listened to Garth Brooks. He was ‘country strong’. From there on out I would run with the D-linemen.

Over the next few practices I started filling in at defensive line when one of the redshirt scholarship guys wanted a break. Before the snap we’d get a crude play (but which was still lightyears beyond anything I did at SHS). I did what I was shown to do, and did what I knew how to do without question: play defensive line. Get the guy with the ball. Crack some heads.

Miami ran a Pro-Style offense. This means passing. We were not a ‘grind it’ kind of team. We could run, but our QB, Geno Torretta, could really air it out to the bevy of talented WRs around him. Because we were Pro-Style, the offensive linemen weren’t hulking behemoths found at run-oriented programs like BIG 10 schools. Instead, our O-linemen were crafty, quick, and smart (the center was the one exception, an unmovable force of squat 350lbs, his legs and butt the largest on the team). A guard who I went against when I moved into tackle or Nose, was Kipp Vickers. At 6’2 280 he wasn’t popping off the charts, but he went onto a long and successful NFL career with the Colts. No matter their size, those guys could hit. They worked well as a unit, and most of all, they had an amazing coach.

Art Kehoe.

Coach Kehoe played for UM in the early 80s, has been around the program for four decades, and put many guys in the NFL. Loud (one of the loudest voices I’ve ever heard) and brash, Coach Kehoe was the most respected and liked coach hands down. He was the unofficial liaison between the staff and the players. Great motivator and honest with his praise, he could also verbally bodyslam a player if he wasn’t performing.

Great players, great coaching. This was the real deal. It was a test unlike any other to not get blown out of the water every play and prove to myself that I could play at the highest level.

So the scout team pretends like it’s the upcoming opponent. Most teams we would play employed a 4-3-4 defense (four linemen, three linebackers and four defensive backs). There were two redshirted scholarship players at D-tackle, and two ends who were looking to get noticed, one of which was Kenny Holmes, a future All-American and big time NFL player.

Because there were seven linebackers (two who were walk-ons) for three positions, if I wanted to get in there, I’d have to play line. It might seem strange to you hearing about a guy wanting to get ‘time’ on the scout team. Truth be told, I wasn’t out there thinking one day I could be playing D-line in a game for the Canes. I just wanted to contribute, help the team win, and not stand there all day doing nothing. My entire sports life no matter what I played, I was always a starter. Not that I’m a super great athlete or anything, but I try hard, give it my all, and hate losing more than I like winning.

What is a good athlete anyway? In my life, I’ve had moments of such athletic greatness it’s hard to believe. People who have witnessed these brilliant flashes of ability have been astonished by them, and I would be too if I wasn’t use to it. Just flashes, though. Flashes. Fashes faster than lightning. So don’t get too excited, okay, not saying I’m some kind of Decathlete.